Index

Index

Pu-erh tea comes exclusively from Yunnan province in China and falls into two main categories: raw (sheng) and ripe (shou). Each type offers distinct flavors that range from fresh and bright to deep and earthy.

This guide will explain the major pu-erh tea types, how they’re made, and help you choose the right one for your taste. Your journey into this fascinating tea tradition starts now.

Key Takeaways

- Pu-erh tea comes exclusively from Yunnan province in China and divides into two main types: raw (sheng) and ripe (shou), each offering distinct flavor profiles.

- Raw pu-erh ages naturally over decades, developing complex flavors, while ripe pu-erh undergoes accelerated fermentation called wet-piling that creates deep, earthy flavors in just weeks.

- True pu-erh requires leaves from the large-leaf Camellia sinensis var. assamica plant, with mountain terroir in Yunnan greatly impacting each tea’s unique character.

- Ancient tree pu-erh teas command higher prices and contain deeper flavors than plantation teas, with scientific studies confirming their superior brewing durability.

- Factory productions use four-digit recipe numbers that reveal the tea’s creation year, leaf grade, and producing factory, helping buyers identify quality levels.

Pu-erh Tea Basics

Pu-erh tea stands apart from other teas through its unique post-fermentation process that creates rich, earthy flavors. This special type of dark tea transforms over time like fine wine, developing deeper complexity and smoother taste with proper aging.

Understanding What Makes Tea “Pu-erh”

True pu-erh tea comes only from Yunnan province in China and must use leaves from the large-leaf Camellia sinensis var. assamica tea plant. The magic happens through a special fermentation process that allows microorganisms to transform the tea over time.

Unlike other teas, pu-erh improves with age much like fine wine, developing deeper flavors and smoother textures as years pass. This unique aging ability has earned pu-erh its reputation as the “elixir of longevity” among tea drinkers.

The geographic origin plays a crucial role in creating authentic pu-erh tea. Mountain terroir in Yunnan impacts each tea’s flavor profile, with variations based on soil, altitude, and climate.

Tea experts recognize two main types: Sheng (raw) pu-erh undergoes natural aging, while Shou (ripe) pu-erh goes through accelerated fermentation to mimic aged characteristics. Both styles get pressed into cakes or bricks for better storage and transport, a tradition dating back centuries along ancient tea trading routes.

Raw vs. Ripe: The Two Paths of Pu-erh

Pu-erh tea follows two distinct paths: raw (sheng) and ripe (shou). Raw pu-erh dates back to the Tang dynasty and ages naturally over many years, developing complex flavors that range from floral to fruity to woody.

This traditional tea can continue to mature for 40-60 years, changing character throughout its lifespan. The aging process relies on natural fermentation, where microbes slowly transform the tea leaves.

Ripe pu-erh, created in the 1950s, offers a different experience through a process called wet-piling. Producers stack tea leaves in warm, moist conditions to speed up fermentation, similar to composting.

This method creates the deep, earthy flavors in just weeks instead of years. Ripe pu’er typically has a shorter aging potential of about 20 years and displays dark colors with smooth, mellow tastes lacking the astringency found in its raw counterpart.

Both styles offer unique qualities that appeal to different tea drinkers.

The Importance of Terroir and Origin

Pu’er tea gains its unique character from Yunnan Province’s special growing conditions. The region’s biodiversity and climate create perfect conditions for large-leaf Dayeh tea trees that have thrived there since 225 BC.

These environmental factors—soil composition, altitude, rainfall, and temperature—give each tea its distinct flavor profile. Just like wine, pu’er tea reflects the exact spot where it grew.

The specific mountains and valleys of Yunnan imprint their signature on every tea leaf. Teas from Yiwu Mountain taste different from those grown in Lincang or Xishuangbanna. Each area produces leaves with unique mineral content, sweetness, and aromatic qualities.

Tea experts can often identify a tea’s origin by taste alone. This connection to place makes pu’er more than just a beverage—it links drinkers to centuries of Chinese tea tradition and the sustainable practices of Yunnan’s tea farmers.

The Role of Microbial Fermentation

Microbial fermentation stands as the heart of pu-erh tea’s unique character. Tiny organisms transform the tea leaves after they’ve been dried and rolled, creating deeper flavors that set pu-erh apart from other tea types.

This natural process breaks down compounds in the leaves, resulting in richer tastes and potentially enhanced health benefits that many tea drinkers seek.

Raw pu-erh develops slowly through years of natural aging, while ripe pu-erh speeds this up through wet-piling techniques. The microbes involved—mainly bacteria and fungi—create the earthy, woody notes that pu-erh fans love.

This biological activity continues even during storage, allowing the tea’s profile to evolve and mature like fine wine.

Understanding Age and Storage Impact

Age transforms pu-erh tea dramatically, creating deeper flavors as time passes. Young raw pu-erh starts bright and astringent, while properly aged tea develops sweet, earthy notes through natural fermentation.

Storage conditions directly shape this aging process. Tea experts maintain humidity between 50% and 75% to ensure optimal development. Too dry, and the tea stagnates; too humid, and unwanted mold may appear.

Temperature also plays a crucial role in how pu-erh matures over decades.

Storage methods vary based on your local climate. Collectors use pumidors (controlled humidity cabinets), ceramic jars, or original packaging to protect their tea investments. Air circulation must balance with stable conditions for the best results.

Some rare aged pu-erh teas sell for hundreds of thousands of dollars, making proper storage both an art and financial consideration. The tea’s quality depends on these storage factors as much as the original leaf material.

Prince Of Peace Premium Pu-erh Tea

A forgiving, no-equipment-needed first step into pu-erh's earthy world.

Pu-erh's earthy, fermented character can be intimidating—but it doesn't have to be. These teabags offer a gentle introduction: 8 reviewers describe the earthiness as present but not overwhelming, and the flavor stays smooth even if you forget to pull the bag on time.

⚠️ Skip this if you're chasing deep, aged complexity—the teabag format prioritizes convenience over the layered flavors of cake-form pu-erh.

Processing Methods and Styles

Pu-erh tea processing methods create distinct flavors through careful steps and timing. Each style—from raw sheng to ripe shou—follows specific techniques that transform the tea leaves into their final form.

Traditional Sheng (Raw) Processing

Traditional Sheng processing starts with fresh tea leaves from Yunnan province. Farmers wither these leaves outdoors, then pan-fry them to halt oxidation—similar to green tea production.

The leaves undergo rolling to break cell walls and release essential oils before drying in the sun. This initial process creates a tea that will transform naturally over time through microbial activity.

Raw pu-erh differs from other teas because it continues to change after production. Fresh Sheng tastes grassy and bitter, requiring at least 10 years of aging to develop complex flavors.

Tea masters compress the processed leaves into cakes, bricks, or other shapes for easier storage and transport during this extended aging period. Modern Shou (ripe) processing takes a different approach by speeding up this natural fermentation.

Modern Shou (Ripe) Processing

Shou pu-erh tea undergoes a special process called “wet piling” that speeds up aging. Tea makers moisten the dried leaves, pile them in large heaps, and turn them regularly to control fermentation.

This method creates the dark color and earthy flavor that many tea lovers enjoy. The process typically takes 45-60 days and transforms the tea’s character completely.

High-quality ripe pu-erh should taste smooth and rich without any fishy or musty notes. The fermentation mimics the natural aging that happens in raw pu-erh but happens much faster.

Many tea enthusiasts appreciate how this process makes the tea more approachable for beginners while still offering complex flavors. The compression techniques used after fermentation create various shapes that affect how the tea will continue to develop over time.

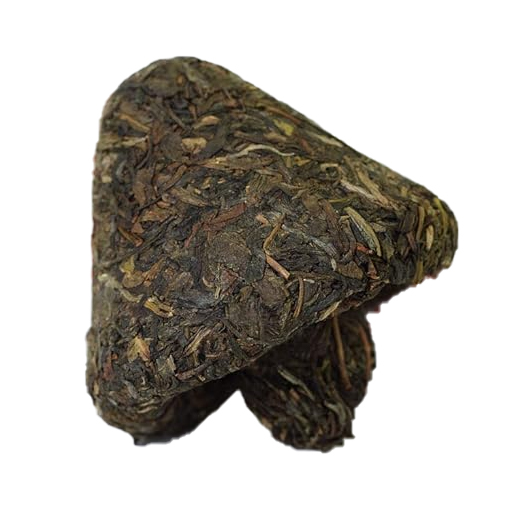

Compression Techniques and Forms

After the ripe processing finishes, pu-erh tea transforms again through compression. Tea masters press the leaves into specific shapes using traditional methods that date back centuries.

The most common form is the Beeng Cha or cake, which typically weighs 357 grams and requires proper storage with good airflow and low light. Other popular shapes include bricks (Zhuan Cha), mushrooms (Jin Cha), nests (Tuo Cha), and loose leaf varieties.

Each compression style serves both practical and artistic purposes in the pu’er world. Bricks stack easily for transport, while the unique design of mushroom shapes helps manage moisture during aging.

The compression tightness affects how the tea ages – looser cakes allow faster air circulation, while tighter forms develop flavor more slowly. Tea enthusiasts often collect different shapes based on their storage space and brewing preferences, with each form offering a distinct aging profile for this fermented tea.

The Art of Fermentation Control

Fermentation control stands as the beating heart of pu-erh tea production. Tea masters must balance moisture, temperature, and time to develop the tea’s signature flavors. For ripe pu-erh, they use the wet-piling method where leaves are moistened, piled, turned, and aired with precision.

This careful process transforms the tea leaves through microbial activity, creating the deep, earthy profiles that tea lovers seek.

Each step requires expert judgment to prevent mold while encouraging beneficial microbes to thrive. The piles need regular turning to maintain even fermentation throughout. Too much moisture creates off-flavors, while too little halts the process entirely.

Master producers can sense the perfect moment to stop fermentation, locking in complex flavors that range from woody and earthy to sweet and fruity. This control separates ordinary tea from exceptional pu’er that improves with age.

Raw Types of Pu-erh

Raw pu-erh tea offers distinct flavor profiles based on age and origin. Young raw teas bring bright, fresh notes while aged varieties develop complex, deep characters. Mountain-specific teas showcase unique traits from their growing regions.

Discover how ancient tree leaves create premium experiences and why tea experts prize certain harvests above others. Ready to explore the fascinating world of raw pu-erh?

Young Raw Pu-erh Characteristics

Young raw pu-erh tea offers a bright flavor profile similar to green tea. These teas, aged less than five years, display distinct floral, sweet, and grassy notes that tea enthusiasts prize.

Mansa Tea’s Yiwu Wild Tree Raw Pu-erh from 2018 serves as a perfect example of this style. The leaves brew into a light yellow liquid with minimal bitterness when prepared using gongfu brewing methods.

Tea experts value young sheng pu’er for its lively character and fresh taste. The quality of these teas depends greatly on the wild tea trees they come from and proper storage conditions.

Gaiwan brewing brings out the best in these specialty teas, allowing drinkers to experience their youthful, grassy qualities through multiple steepings. Unlike fully aged varieties, these younger versions showcase the original terroir more clearly.

Semi-Aged Raw Profiles (5-10 years)

Semi-aged raw pu-erh represents only 10-15% of the pu-erh market, making these teas somewhat rare finds for collectors. These teas strike a perfect balance between the sharp astringency of young sheng and the mellow depth of fully aged varieties.

After 5-10 years of proper storage, the tea leaves develop honey-like sweetness and a smooth mouthfeel while maintaining some of their original vibrancy and character.

The quality of semi-aged raw pu-erh depends greatly on storage conditions and the initial leaf quality. Weak teas simply don’t age well under traditional wet storage methods, often losing their distinct profiles instead of gaining complexity.

Tea enthusiasts prize these middle-aged pu-erhs for their approachable flavor profiles that hint at what they might become with another decade of aging. Many tea shops sell these as gateway teas for newcomers to aged raw pu-erh.

Fully Aged Raw Varieties (10+ years)

Fully aged raw Pu’er teas offer tea lovers a rare taste experience after at least a decade of proper storage. These teas contain remarkably high polyphenol levels—reaching 210.2 mg GAE/g—which develop through natural aging processes.

The leaves transform gradually, creating deeper flavors with notes of dried fruits, wood, and earth that simply don’t exist in younger versions. Many collectors prize these teas for both their complex taste profiles and potential health benefits, as studies link aged Pu’er to improved digestive health.

The most treasured raw Pu’er teas can continue aging for up to 50 years, gaining value and changing character throughout their lifespan. Brewing these precious teas requires specific techniques—water at 90°C for exactly 5 minutes extracts the optimal balance of flavors and beneficial compounds.

Tea experts can identify authentic aged specimens by examining leaf appearance, aroma, and the liquid’s color and texture. Next, we’ll explore the unique characteristics of single mountain specialties that contribute to the diverse world of Pu’er tea.

Single Mountain Specialties

Single mountain pu-erh teas offer unique flavor profiles based on their specific origin. Yiwu Mountain teas typically deliver gentle, sweet notes with hints of dried fruits, while Bulang Mountain varieties pack more punch with their bold, bitter qualities that mellow with age.

Nannuo Mountain styles stand out for their honey-like sweetness and distinct floral character that tea lovers prize.

Jingmai ancient tree teas showcase their complex mineral notes and lingering sweetness that comes from trees hundreds of years old. These regional differences result from each mountain’s unique soil composition, elevation, and microclimate.

Tea enthusiasts often develop preferences for specific mountain origins, with some collectors focusing exclusively on prestigious areas like Lao Banzhang, where the quality tea commands premium prices in the market.

Ancient Tree Classifications

Ancient tree (AT) pu-erh teas stand apart from their terrace tea (TT) counterparts in several key ways. These prized teas grow in sustainable ancient gardens throughout Yunnan Province, producing leaves with deeper flavors and more distinct aromas than regular plantation teas.

Research comparing 30 AT samples against 50 TT varieties confirmed these differences through scientific analysis. Tea experts value ancient tree pu-erh for its superior brewing durability and complex taste profile that develops with age.

Buyers should know that spotting genuine ancient tree tea presents challenges in today’s market. Many sellers mislabel terrace tea as ancient tree to command higher prices. The rich character of true ancient tree pu-erh comes from older root systems that draw nutrients from deeper soil layers.

These trees, often growing wild or semi-wild, produce tea leaves that contain unique compounds not found in younger plantation bushes. The most famous ancient tree classifications come from renowned mountains like Lao Banzhang, Yiwu, and Bulang.

Ripe Pu-erh Varieties

Ripe Pu-erh varieties offer a rich landscape of flavors from classic factory productions to modern craft styles, each with distinct profiles shaped by fermentation techniques and regional influences – discover how recipe numbers and quality grades can guide your selection of these dark, earthy teas.

Classic Factory Productions

Menghai Tea Factory stands as a cornerstone in Pu-erh production since 1940, making it one of Yunnan’s oldest specialized tea facilities. This historic factory crafts an impressive range of products – 12 varieties of raw Pu-erh and 57 types of ripe Pu-erh teas.

The factory made tea history in 1973 by creating the ‘wodui’ method, which revolutionized how ripe Pu-erh ages. You’ll notice many Menghai products feature the ‘dayi’ logo, which translates to “great benefit” and signals the tea’s health properties.

Their vintage Pu-erh cakes showcase the robust, earthy profiles that tea enthusiasts prize in traditional Chinese tea. These classic productions serve as benchmarks against which other Pu-erh teas are often measured.

The distinct grade systems used by Menghai help buyers identify quality levels across their extensive product line. Next, we’ll explore the traditional recipe numbers that guide these classic productions.

Traditional Recipe Numbers

Factory productions lead us to the coded language of Pu-erh: the recipe numbers. These four-digit codes tell a tea’s complete story at a glance. The first two digits mark the year the recipe was created, while the third number indicates leaf grade (with lower numbers signifying higher quality).

The fourth digit reveals which factory produced the tea. Tea enthusiasts prize certain formulations above others – Dayi’s raw recipes 7532, 7542, and 8582 have earned legendary status among collectors.

Xiaguan’s 8653 recipe also commands respect in the Pu-erh market.

These numbers function like a DNA sequence for each tea cake, helping buyers identify exactly what they’re purchasing. Most serious Pu-erh drinkers learn to recognize famous recipes by their numbers alone.

The grade digit proves especially important – it tells you whether you’re getting premium buds or larger, less refined leaves. For example, a “3” in the third position signals a blend with smaller, more tender leaves than a “5” or “7” in the same spot.

Modern Craft Styles

Modern craft styles of ripe pu-erh tea break away from traditional factory methods. Tea artisans now focus on creating high-quality products with careful attention to leaf selection and fermentation control.

These craftspeople adjust humidity, temperature, and timing to develop sweet, floral notes while reducing the heavy earthiness found in mass-produced varieties. Many small-batch producers use ancient tree materials and precise fermentation techniques to create smoother, richer flavor profiles that appeal to tea enthusiasts worldwide.

Quality stands as the defining feature of these craft productions. The best modern ripe pu-erh teas offer complex taste experiences without the muddy or fishy notes sometimes found in lower-grade options.

Tea masters carefully monitor each step of the process to ensure optimal microbial activity during fermentation. This attention to detail creates teas with remarkable depth, smoothness, and aging potential.

Traditional recipe numbers help buyers identify specific flavor profiles within the expanding world of quality grade classifications.

Quality Grade Classifications

Pu-erh tea follows a specific grading system ranging from 1 to 10, with lower numbers marking higher quality. Grade 1 teas typically feature perfect bud-to-leaf ratios—one bud with two leaves—harvested during the prized Ming Qian spring season.

These premium grades display more refined flavors and command higher prices in the market. Tea producers evaluate multiple factors during grading, including leaf freshness, harvest timing, and growing region within Yunnan province.

Smart tea buyers learn to spot quality markers in both raw and ripe pu-erh varieties. The leaf quality directly impacts the tea’s infusion color, aroma profile, and aging potential.

Top-grade pu’er cakes often contain more buds and tender leaves, creating smoother mouthfeel and complex flavor notes. Factory productions typically include grade information in their traditional recipe numbers, helping consumers make informed choices about their tea purchases.

Regional Varieties from Yunnan

Yunnan province stands as the birthplace of pu-erh tea, with each region creating distinct flavor profiles based on local growing conditions. The mountains, soil, and climate shape these teas, giving each area its own special character that tea fans can taste and identify.

Six Famous Tea Mountains

The Six Famous Tea Mountains represent the most prestigious pu-erh growing regions in China. These mountains – Yiwu, Yibang, Youle, Gedeng, Manzhuan, and Mansa – each produce tea with distinct flavor profiles.

Yiwu and Yibang stand at the top for their exceptional quality, with Yiwu ranking first in tea-tasting events. Tea from these mountains comes from spring leaves grown without pesticides or fertilizers, making them highly sought after by tea lovers.

The limited production of only 2000 sets annually makes these teas rare treasures in the pu-erh world. Each mountain contributes unique characteristics to the tea: Yiwu offers delicate sweetness, Yibang brings floral notes, while Youle provides robust body.

The final ranking established through expert evaluation places Yiwu first, followed by Yibang, Youle, Mansa, Manzhuan, and Gedeng. This ranking helps tea drinkers understand the quality hierarchy within these famous growing areas.

Menghai Region Classics: Robust, earthy profiles

Menghai Region produces some of the most respected Pu-erh teas in Yunnan province. Since pioneering the ‘wodui’ ripening method in 1973, Menghai Tea Factory has created teas known for their distinct robust character and deep earthy flavors.

These classic productions often display rich, loamy notes with hints of dark wood and aged leather that tea enthusiasts prize. The factory’s signature “dayi” logo—meaning “great benefit”—appears on many cakes and signals quality to buyers seeking authentic regional styles.

Tea from this area gains its unique profile from local soil conditions and traditional processing techniques passed down through generations. Menghai Pu-erh typically offers fuller body than other regional varieties, with a smoothness that develops through proper aging.

Both raw and ripe styles showcase the region’s characteristic strength, though each follows different fermentation paths. Next, we’ll explore the distinctive qualities of Lincang Area Productions with their mineral-rich profiles.

Lincang Area Productions: Mineral-rich, bold character

Lincang produces some of the most distinctive pu-erh teas in Yunnan, prized for their mineral-rich profiles and bold character. These teas come from the ‘Da Ye Zhong’ large leaf varietal, which thrives in the region’s warm, humid climate.

Tea drinkers often note the thick mouthfeel and strong energy that sets Lincang puer apart from other regional varieties. The area boasts an impressive tea cultivation history exceeding 2,000 years, making it a cornerstone of Chinese tea culture.

Tea farmers in Lincang craft both raw and ripened pu-erh with unique qualities that reflect the local terroir. The soil composition gives these teas their signature mineral notes, while proper processing brings out their full-bodied taste.

During annual tea festivals, locals celebrate this rich heritage through tastings and cultural events. Many collectors seek out Lincang loose leaf tea for both drinking pleasure and aging potential, as these teas develop complex flavors over time.

Xishuangbanna Varieties: Floral, tropical notes

Xishuangbanna sits at the southernmost tip of Yunnan province, sharing borders with Myanmar and Laos. This unique location creates perfect growing conditions for some of China’s most prized pu’er teas.

The region’s rich biodiversity and tropical climate give these teas distinct floral aromas and fruit-like flavors not found in other pu-erh varieties. Many tea experts prize Xishuangbanna productions for their honey-sweet undertones and smooth mouthfeel that develops with proper aging.

The quality of Xishuangbanna tea comes from its special terroir – the combination of soil, climate, and elevation that shapes flavor. Tea gardens here benefit from misty mornings, warm days, and cool nights that slow leaf growth and concentrate flavor compounds.

Both raw and ripe pu-erh from this area display exceptional complexity, with young sheng (raw) teas offering bright, tropical fruit notes that transform into deeper, more nuanced profiles as they age.

The best examples balance natural sweetness with a pleasant astringency that tea collectors eagerly seek.

FullChea Puerh Tea Cakes 2008/2018 Menghai

An affordable entry to Menghai terroir—floral, fresh, and suitable for aging experiments.

Menghai county sits at the heart of Yunnan's pu-erh production—a region known for robust, earthy character with clean fermentation. This cake from Menghai offers a chance to taste what the region produces: floral aromatics, a fresh finish, and approachable pricing for those beginning to explore terroir.

⚠️ Skip this if you're expecting the deep, aged complexity of decade-old sheng—this is young tea with potential, not peak maturity.

Mountain-Specific Characteristics

Each mountain in Yunnan gives its tea a unique flavor profile that tea lovers can learn to spot. Yiwu teas bring honey sweetness, while Bulang offers bold bitterness that transforms with age.

Yiwu Mountain Teas

Yiwu Mountain teas rank among the most prized pu-erh varieties in the tea world. These organic, artisanal teas grow in the famous Six Ancient Tea Mountains region of Xishuangbanna, where perfect growing conditions create their distinct character.

The 2017 Yiwu Mountain Raw Pu-erh showcases dark green, plump leaves that produce a clear orange-yellow liquid with an oily texture that tea lovers seek.

The flavor profile of Yiwu teas sets them apart from other regional pu-erhs. They offer floral and fruity aromas that balance with a rich taste many collectors value. The cake form features a dark, shiny appearance with thick cords that mark quality processing.

Many tea experts consider Yiwu pu-erh the perfect starting point for new drinkers because it delivers complex flavors without the harsh bitterness found in other mountain varieties.

Bulang Mountain Varieties

Bulang Mountain tea stands out in the pu-erh world with its powerful character and distinct bitter notes. Located in Xishuangbanna at high elevations, this region produces the famous Laobanzhang pu-erh, prized by collectors worldwide.

Local tea workers craft these unique varieties through traditional hand-roasting methods, preserving techniques passed down through generations. The mountain’s remote location, with difficult road access, has helped maintain the authenticity of its tea production.

Bulang Mountain pu-erh delivers an intense drinking experience with strong chaqi (tea energy) that tea enthusiasts seek. The teas often show a bold bitterness that transforms into sweetness, making them excellent candidates for aging.

These qualities come from the ancient tea trees growing in the mineral-rich soil of the region. Next, we’ll explore how Jingmai Ancient Tree Teas compare to these robust Bulang varieties.

Nannuo Mountain Styles

Nannuo Mountain pu-erh teas stand out in the tea world with their unique flavor profile. Located in Menghai County at 1400 meters elevation, these teas develop distinct tastes that tea lovers seek.

The gardens of Shitouzhai village produce leaves with an initial bitter bite that quickly transforms into a pleasant aftertaste called “huigan.” This smooth transition makes Nannuo pu-erh special among other tea types.

The clean, honey-orchid fragrance fills your cup with each steep, creating a sensory experience unlike other regional varieties.

The quality of Nannuo Mountain tea comes from its specific growing conditions and traditional processing methods. The higher altitude creates stress on the tea plants, resulting in more complex flavors than lower elevation teas.

Many collectors prize these teas for their balanced character – neither too aggressive like some Bulang varieties nor too delicate like other mountain styles. The dry tea leaves often show a beautiful mix of colors that hint at their rich flavor profile.

Jingmai Ancient Tree teas offer another fascinating mountain profile worth exploring next.

Jingmai Ancient Tree Teas

Jingmai Mountain boasts tea trees that range from hundreds to thousands of years old, creating some of China’s most prized pu-erh varieties. These ancient gardens date back nearly 2,000 years, earning such respect that Jingmai teas became royal tributes during the Ming Dynasty.

The mountain’s unique ecology gives these teas their signature strong fragrance with remarkably low astringency – qualities tea collectors eagerly seek. Popular types include Jingmai Dazhai, Mang Jing Cun, and Nuogang, each offering distinct flavor profiles while maintaining the region’s characteristic sweet finish.

The age of these tea trees directly impacts the brewing experience, with older specimens producing more complex cups and greater staying power through multiple steepings. Many tea experts consider the ancient tree designation (typically 100+ years) as a mark of superior quality, though this status also drives higher prices in the market.

Next, we’ll explore the distinct characteristics found in teas from Nannuo Mountain, which offers its own special terroir influence.

Lao Banzhang Prestige

Lao Ban Zhang stands as the crown jewel of pu-erh tea, earning a reputation similar to Champagne in the wine world. This prestigious tea grows on ancient trees in the Bulang Mountains, where Master Gao crafts each batch using time-honored methods.

The leaves produce a complex flavor that expands through multiple steepings, revealing new taste dimensions with each cup.

The village has seen major economic growth thanks to this prized tea. Tea experts prize Lao Ban Zhang for its unique character that comes from the mountain’s specific growing conditions.

The tea commands high prices at market, making it both a luxury drink and status symbol among serious tea collectors. Its distinct profile includes notes that cannot be found in teas from other regions.

TWG Emperor Pu-Erh Tea

Premium whole-leaf pu-erh in collectible packaging—when presentation matters as much as taste.

Luxury pu-erh often means paying for provenance—specific mountains, ancient trees, and meticulous processing. TWG's Emperor Pu-Erh represents premium positioning: whole leaves, robust flavor, and the kind of presentation that works for gifting or building a high-end collection.

⚠️ Skip this if you need a daily drinker—at $40 for 100g, this is ceremonial-grade pricing for focused sessions, not casual sipping.

Age and Storage Categories

Pu-erh tea changes dramatically based on how it ages and where it’s stored. Different storage methods create distinct flavor profiles that range from earthy and woody to sweet and fruity.

Traditional Hong Kong Storage

Hong Kong storage represents one of the most famous aging methods for pu-erh tea. Tea merchants in Hong Kong pioneered specific storage techniques that expose tea cakes to higher humidity levels (70-80%) and warmer temperatures.

This environment speeds up the fermentation process, creating deeper, more complex flavors in a shorter time frame. Tea stored this way often develops distinct notes of earth, wood, and medicinal herbs that many collectors prize.

The traditional cellars used in Hong Kong typically measure between 70 to 120 square meters and lack windows to maintain consistent conditions. These spaces can reach high temperatures that transform the tea’s character significantly.

Many tea experts rotate their stock carefully within these cellars to prevent over-fermentation, as excessive heat can diminish pu-erh’s original qualities. This storage style creates a stark contrast to drier storage methods and produces tea that appears darker in color with smoother textures.

Dry Storage Techniques

Dry storage creates ideal conditions for pu-erh tea to age naturally and develop complex flavors. Tea enthusiasts maintain humidity levels at 70% or below, with temperatures between 70-75°F to prevent mold growth while allowing gentle fermentation.

Good airflow matters greatly—proper ventilation lets the tea breathe without exposing it to harsh elements or strong odors. Many collectors prefer tightly compressed forms like Iron Tea Cakes or Tea Bricks because these shapes preserve moisture better during long-term aging.

Moisture balance stands as the key factor in successful dry storage. Tea leaves containing more than 14% moisture risk developing unwanted mold, while those with less than 7% stop fermenting altogether.

This delicate balance explains why serious puerh collectors invest in humidity monitors and storage containers designed specifically for tea preservation. Traditional Chinese tea masters often store their prized cakes in unglazed clay vessels that regulate moisture naturally, a practice dating back centuries in tea-producing regions of Yunnan.

Wet Storage Characteristics

Wet storage creates distinct flavors in pu-erh tea through artificially moist conditions. This method speeds up aging and develops deeper, earthier profiles with less astringency. Tea shops in Hong Kong and Macau commonly use this technique, which has earned the nickname “Hong Kong storage” among Taiwanese tea circles.

The process encourages specific microbial growth that transforms the tea leaves, resulting in darker brews with medicinal notes and smooth mouthfeel.

Northern Chinese tea enthusiasts often avoid wet-stored pu-erh, preferring the slower, more controlled dry storage method. The microclimates during storage play a crucial role in shaping the final taste profile.

Wet-stored teas typically show darker leaf colors, more pronounced humidity aromas, and less bitterness than their dry-stored counterparts. These teas brew up black in color rather than amber, making them easy to identify in a tasting.

Natural Aging Methods

Natural aging lets pu-erh tea develop complex flavors through time alone. Tea masters store their cakes in clean, stable environments with proper airflow and humidity levels between 60-70%.

This method takes patience—quality pu-erh often matures for 10-30 years before reaching its peak character. Unlike forced techniques, natural aging preserves the tea’s original mountain character while allowing subtle microbial changes to enhance its depth.

Many collectors prefer this traditional approach because it creates more balanced profiles with less risk of off-flavors or mold issues that can plague wet storage methods.

The aging process transforms raw pu-erh from astringent and grassy to smooth and earthy through gradual oxidation. External factors like temperature shifts between seasons play an important role in this transformation.

Tea enthusiasts in China and Taiwan often rotate storage positions yearly to ensure even aging throughout each cake. This slow maturation develops honey, fruit, and wood notes that simply cannot exist in fresh tea leaves.

The best naturally-aged pu’erh teas command high prices due to their rarity and the decades of care invested in their creation.

Shapes and Compression Styles

Pu-erh tea comes in many shapes beyond the common disc, from small bowl-shaped tuo cha to rectangular bricks, each with its own aging profile and storage needs – read on to discover which form might best suit your taste and space limits.

Traditional Cake (Beeng Cha)

Traditional cake, or Beeng Cha, stands as the most iconic form of compressed pu-erh tea. Each disc typically weighs exactly 357 grams (about 12.6 ounces), a standard that dates back to imperial measurement systems.

Tea artisans press the leaves into round cakes using both mechanical methods and hand techniques, creating a flat disc with slightly raised edges that allows for proper aging while making storage and transport easier.

You can identify quality Beeng Cha by examining its compression level – neither too tight nor too loose. The best cakes break apart in chunks rather than crumbling into dust. Many collectors prize these traditional discs for their aging potential, as the cake format creates ideal conditions for the microbial activity that transforms the tea’s flavor profile over time.

The shape also helps protect delicate tea leaves during shipping across vast distances from Yunnan to tea markets worldwide.

Bowl Shapes (Tuo Cha)

Tuo Cha represents one of pu-erh tea’s most distinctive forms, shaped like small bowls or nests that typically weigh between 100-250 grams. Tea producers create these compact shapes by pressing tea leaves into round molds, resulting in a dome-shaped cake with a depression in the center.

This unique design serves a practical purpose – Tuo Cha forms were specifically created for ease of transport along ancient tea trading routes through Tibet and Mongolia. The bowl shape allows merchants to stack these tea cakes efficiently while protecting the leaves from damage during long journeys.

You’ll find Tuo Cha in both raw and ripe pu-erh varieties, with many tea enthusiasts noting that the tighter compression can influence aging patterns differently than traditional flat cakes.

The dense packing means air penetrates more slowly, often creating interesting flavor variations between the outer and inner portions of the tea. Breaking apart Tuo Cha requires special care – tea lovers typically use a pu-erh knife to gently pry off small sections rather than forcing the compressed leaves apart.

Next, we’ll explore the distinctive mushroom styles known as Jin Cha, which offer yet another approach to pu-erh compression.

Brick Forms (Zhuan Cha)

Brick-shaped pu-erh tea (Zhuan Cha) offers tea lovers the most efficient storage option among all compressed tea forms. These rectangular blocks stack neatly in tea cabinets, allowing collectors to maximize their space while aging multiple varieties.

Tea producers press leaves tightly into brick molds using traditional methods that date back centuries in Chinese tea culture. The dense compression of Zhuan Cha creates unique aging conditions inside the brick, often resulting in different flavor development compared to cake or bowl shapes.

Tea enthusiasts prize these bricks for their practical benefits beyond storage. The compact shape makes them easy to transport and break apart for brewing. Many black tea and pu-erh collectors specifically seek aged Zhuan Cha for its distinct character that develops through the aging process.

The compression technique affects how air circulates through the tea, which plays an important role in how the flavors mature over time. Unlike green tea, properly stored pu-erh bricks can improve for decades.

Mushroom Styles (Jin Cha)

While brick forms offer compact storage, mushroom-style pu-erh (Jin Cha) presents a unique shape with practical benefits. Jin Cha resembles small mushrooms with dome-shaped tops and flat bottoms, making them easy to stack and store.

Tea producers create this distinctive form by wrapping tea leaves in cotton cloth and tying them tightly with string, giving the compressed tea its mushroom-like appearance. These shapes manage moisture better than other forms due to their balanced compression and surface area.

Mushroom styles typically weigh between 100-250 grams, making them perfect for tea drinkers who want to sample different pu-erh varieties without committing to larger cakes. The compression technique allows proper air circulation while protecting the tea from excess humidity.

Tea enthusiasts prize Jin Cha for both its practical storage advantages and its traditional Chinese character. Proper storage conditions remain essential for maintaining quality regardless of shape, as even the best Jin Cha will deteriorate under poor conditions.

Ball Shapes (Dragon Balls)

Ball-shaped pu-erh gives you a convenient single-serving option that combines practical brewing with artistic appeal. These compressed spheres typically weigh between 5-10 grams each, making them perfect for your individual brewing sessions without breaking apart larger cakes. We’ve found that premium versions called “Dragon Balls” often contain high-quality leaves from renowned areas like Bingdao Village or Lao Ban Zhang, delivering complex flavor profiles in a compact form.

When you examine these tea balls, you’ll notice their tight compression creates unique aging conditions that develop distinct honey, fruit, and earthy notes over time. The dense packing helps preserve delicate aromas longer than loosely compressed forms. You might also encounter specialty varieties featuring pu-erh packed inside dried tangerine peels, which adds bright citrus characteristics while providing natural protection during aging. Tea collectors prize these miniature spheres for both their concentrated character and space-efficient storage in tea cabinets.

Understanding Quality & Tasting

Pu-erh tea quality shows itself through specific leaf traits and tasting notes that change with age. You can learn to spot real pu-erh from fakes by examining leaf texture, aroma depth, and how the tea develops across multiple steepings.

Evaluating Leaf Quality

Quality pu-erh tea leaves reveal their story through visual cues. The best raw pu-erh displays whole, intact leaves with consistent coloration and minimal breakage. You can spot premium grades by their plump buds and first leaves, which contain higher concentrations of flavor compounds.

The dry leaves should feel slightly springy rather than brittle, indicating proper moisture content and storage conditions. Factory-produced teas often use a grading system based on leaf size, with higher numbers (like grade 1) containing more buds and smaller leaves.

The aroma of dry leaves offers your first clue about fermentation quality. Fresh sheng pu-erh carries grassy, floral notes, while aged varieties develop woody, fruity scents. Ripe pu-erh should smell earthy without any mustiness that might signal poor storage.

After brewing, examine the wet leaves for uniformity, flexibility, and color—properly processed tea leaves unfurl completely and show their mountain origins through distinctive characteristics.

Next, we’ll explore how to identify key age indicators in your pu-erh collection.

Identifying Age Indicators

Beyond leaf quality, a pu-erh tea’s age reveals itself through specific visual and taste markers. Older teas typically display darker leaf colors, ranging from deep amber to mahogany, compared to the greener hues of younger varieties.

The aroma evolves from fresh, grassy notes in new teas to complex woody, earthy, or dried fruit scents in aged specimens.

Taste provides the most reliable age indicators, with young raw pu-erh offering sharp, astringent qualities that mellow into smooth, sweet profiles over time. The tea liquor darkens from pale gold to deep ruby or coffee-brown as decades pass.

Experienced drinkers notice how the mouthfeel transforms from thin and bright to thick and silky—a change impossible to fake through artificial means. These natural transformations happen through microbial activity that breaks down tea compounds during proper storage conditions.

Authenticity Assessment

Genuine pu-erh tea shows specific markers that separate it from counterfeits. The leaf quality speaks volumes – authentic pu-erh displays consistent leaf size with clear veins and stems that match its claimed age.

True aged cakes develop a dark brown color with slight reddish tints, while fakes often appear too uniform or artificially darkened. The aroma test reveals much truth – real pu-erh gives off complex scents that change through brewing stages, not the flat or artificial smells found in imitations.

Many collectors examine compression patterns, as traditional cakes show slight variations in density that machine-made fakes cannot replicate.

You can spot authentic pu-erh by its taste profile too. Real aged tea delivers multiple flavor waves that transform across steepings, starting with woody notes and developing sweetness.

Fake versions typically lack this complexity and fade quickly after the first brewing. The tea liquor should match its age – young raw pu-erh appears golden yellow while properly aged versions show deep amber to reddish hues.

Factory stamps, wrapper designs, and production codes provide additional verification points for serious collectors. Professional tasting methods build on these authenticity checks to fully evaluate the tea’s quality and character.

Storage Condition Analysis

Beyond spotting fake teas, you must assess how a pu-erh has been stored to understand its true character. Storage conditions directly shape a tea’s flavor profile and aging potential.

Proper pu-erh storage requires specific humidity levels (60-80%) and stable temperatures (60-75°F) to support healthy microbial activity. You can detect poor storage through telltale signs like musty odors, mold spots, or unusually dry leaves that crumble easily.

Tea experts examine the cake compression, leaf color variation, and aroma layers to determine storage history. Dry-stored pu-erhs maintain more fresh, floral notes while developing slower.

Wet-stored varieties show darker leaves, deeper earthy flavors, and faster aging patterns. The best pu-erh collections balance these factors, creating ideal environments where teas can mature gracefully without spoiling or stalling in their development.

Professional Tasting Methods

Professional tea tasters evaluate pu-erh using specific techniques that focus on five key elements: appearance, aroma, taste, mouthfeel, and finish. They examine dry leaves for color uniformity and compression quality before brewing multiple infusions in small gaiwans.

Expert tasters slurp tea loudly to aerate it across their palate, noting flavor transitions from early sweetness to later mineral or woody notes.

Tea masters record their findings on standardized evaluation sheets, scoring attributes like clarity, complexity, and aftertaste persistence. They pay special attention to the hui gan (returning sweetness) and cha qi (tea energy) unique to aged pu-erh varieties.

Many professionals cleanse their palates with water between samples and limit tastings to morning hours when sensitivity peaks. This methodical approach helps distinguish authentic mountain-specific characteristics from mass-produced alternatives.

Advanced Brewing Techniques

Mastering pu-erh brewing takes your tea experience to new heights. The right techniques reveal hidden flavors and aromas that casual brewing methods miss.

Temperature and Time Control

Brewing pu-erh tea demands precise temperature control for optimal flavor extraction. Raw pu-erh (sheng) needs water between 185-195°F to prevent bitterness, while ripe pu-erh (shou) performs best with near-boiling water at 200-212°F.

Your steep time varies based on the tea’s age and processing method. Young raw pu-erh requires shorter steeps of 10-15 seconds initially, while aged varieties and ripe pu-erh can handle longer infusions of 20-30 seconds.

Each successive steep should increase by 5-10 seconds to match the changing flavor profile as leaves gradually open.

Tea experts adjust these parameters based on leaf quality and compression style. Tightly compressed cakes need hotter water and longer steeps than loose leaf versions of the same tea.

The water you use matters too – mineral content affects how flavors develop during brewing. Many tea drinkers keep brewing notes to track their preferred parameters for each pu-erh in their collection.

Multiple steeping progressions reveal how pu-erh transforms through numerous infusions, with some quality teas delivering 15+ distinct steeps from a single portion of leaves.

Multiple Steeping Progressions

Pu-erh tea reveals its complex character through multiple steepings, with each infusion offering different flavor profiles. Most quality pu-erh teas yield 8-12 infusions, starting with a quick 5-10 second steep and gradually increasing time with each round.

The first steep often tastes light and subtle, while middle steepings (3-7) deliver the richest flavors and deepest aromas. Raw pu-erh typically changes from bright and grassy to sweet and fruity, while ripe varieties transform from earthy to smooth chocolate notes.

Tea enthusiasts track these flavor shifts using tasting journals or digital apps, noting how each steep changes in color, aroma, and taste. The progression varies based on tea age, storage conditions, and brewing temperature—older teas generally require longer steeping times than younger ones.

Many tea shops in Yunnan province serve customers the same leaves throughout the day, demonstrating how pu-erh tea’s character evolves across numerous infusions. This traditional approach maximizes both value and the full experience of this special type of tea.

Traditional Gongfu Method

The Gongfu brewing technique brings out the best flavors in pu-erh tea through precise steps and special tools. You’ll need a small clay teapot, a serving pitcher, tiny cups, and a tea tray to catch spills.

Tea masters use high leaf-to-water ratios—typically filling the teapot one-third full with leaves. They rinse the leaves briefly with hot water before the first true steep, which might last only 5-10 seconds.

Each following steep increases by a few seconds, allowing you to experience how the tea’s character changes across multiple infusions.

The beauty of Gongfu lies in its attention to detail—water temperature matters greatly for pu-erh, with most varieties requiring water just off boiling (95-100°C). This method reveals subtle notes in both raw and ripe pu-erh that casual brewing might miss.

Many tea enthusiasts find that aged teas respond especially well to Gongfu preparation, showing deeper complexity with each cup. Water quality plays a crucial role in bringing out the true character of your tea.

Water Quality Importance

Water makes or breaks your pu-erh tea experience. Pure spring water brings out the sweet, complex notes in aged pu-erh that tap water often masks. The mineral content matters greatly – calcium and magnesium enhance body while excessive iron or chlorine ruins delicate flavors.

Many tea masters insist on using specific mountain springs for brewing premium pu-erh, as these waters complement the tea’s natural profile.

Testing your home water can improve your brewing results dramatically. Hard water tends to flatten pu-erh’s subtle characteristics, while soft water allows its aged complexity to shine through.

Filtered water offers a good compromise for most tea drinkers. Each pu-erh variety responds differently to water quality – ripe puer needs slightly harder water than its raw counterparts to balance its earthy depth.

Brewing Ball-Shaped Pu-erh

Ball-shaped pu-erh requires special brewing attention due to its exceptionally tight compression. You’ll find these dense spheres initially resist water penetration, requiring modified techniques to unlock their full flavor potential. We recommend starting with a longer initial rinse of 30 seconds using boiling water (100°C), then letting the ball rest in a covered vessel for several minutes. This steam bath helps loosen the compressed leaves before your first proper infusion.

For particularly stubborn Dragon Balls, you can gently break or pry apart the sphere after initial steeping to improve extraction. Many tea enthusiasts employ a thermos method for these compressed forms, allowing extended contact time of 30+ minutes to fully release flavors from the dense center. Your patience will be rewarded with remarkable complexity that unfolds throughout multiple infusions—you’ll experience how the flavor transforms from bright and floral in early steeps to deep and smooth in later rounds, often yielding 8-12 distinctive cups from a single ball.

COSORI Electric Gooseneck Kettle with Temperature Control

Temperature presets and hour-long hold for navigating the full pu-erh spectrum without guesswork.

Pu-erh brewing temperature matters: young sheng needs cooler water (around 185°F) to avoid harsh bitterness, while aged cakes and ripe shou can handle near-boiling temperatures. This gooseneck kettle offers 5 presets covering that range, with a temperature hold function for extended gongfu sessions.

⚠️ Skip this if you're brewing for a crowd—the smaller capacity means refilling between rounds when hosting tea sessions.

The Culture of Pu-erh Tea

Pu-erh tea connects people across generations through shared rituals and knowledge passed down for centuries. Tea collectors value aged pu-erh cakes as both cultural treasures and financial assets, similar to how wine enthusiasts collect rare vintages.

Historical Significance

Pu-erh tea holds a treasured place in Chinese culture dating back to the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE). Merchants transported this prized tea along ancient trade routes, creating the famous “Tea Horse Road” that connected Yunnan to Tibet and beyond.

The tea served as currency and vital nutrition for Tibetan people who lacked vegetables in their diet. During the Ming Dynasty, imperial courts favored pu-erh for its unique taste and medicinal properties, with some rare cakes becoming family heirlooms passed through generations.

Tea collectors today seek vintage pu-erh cakes from the 1950s-1970s, which can fetch thousands of dollars at auction. The most famous example occurred in 2002 when a 500g cake of 1920s “Antique Tong Qing Hao” sold for $28,000 in Hong Kong.

This investment aspect adds another layer to pu-erh’s cultural importance. The modern market evolution shows how this ancient beverage continues to adapt while maintaining its deep cultural roots.

Collection and Investment

Many tea lovers build Pu-erh collections as both passion projects and financial assets. Aged cakes from the 1950s can fetch thousands of dollars at auction, with prices rising steadily for well-stored examples.

Serious collectors focus on specific regions like Lao Banzhang or Yiwu Mountain, tracking how flavors develop over decades. Smart investors purchase multiple cakes of promising young Sheng Pu-erh, storing some for personal enjoyment while holding others as long-term investments.

The market has grown more sophisticated since 2000, with collectors demanding clear documentation of age, origin, and storage conditions before making major purchases. The growing interest in Pu-erh’s cultural significance has created new opportunities for both casual and serious tea enthusiasts to explore its rich traditions.

Modern Market Evolution

Pu-erh tea markets have transformed dramatically since 2000. Online platforms now connect tea farmers directly with global buyers, bypassing traditional distribution chains. This shift has created both opportunities and challenges for consumers.

Prices for premium ancient tree teas have jumped tenfold in some cases, while counterfeit products flood lower market segments.

Tea auctions in China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan now set benchmark prices for rare pu-erh cakes. Social media groups and tea forums shape buying trends and educate new drinkers about quality standards.

Factory productions still dominate sales volume, but small-batch artisanal pu-erh teas gain popularity among western tea enthusiasts. The market now splits between investment-grade teas stored for future value and daily-drinking varieties that offer quality at reasonable prices.

Conclusion

Your pu-erh journey offers endless paths through raw and ripe varieties, each with unique stories to tell. From young sheng with bright, bold flavors to aged shou with deep, earthy notes, these teas reward patient exploration.

The mountains of Yunnan imprint their character on every leaf, creating distinct regional profiles worth discovering. Tea shapes – from classic cakes to tight bricks – each age differently and reveal their secrets at their own pace.

As you taste more varieties, your palate will develop, allowing you to appreciate the subtle differences that make pu-erh so special.

FAQs

1. What are the different types of pu-erh tea?

Pu-erh tea comes in various types based on how it’s processed. We classify them mainly as raw (sheng) and ripe (shou), with different grades and shapes sold in the market. The quality of the tea depends on the conditions during processing and the aging period.

2. How does pu-erh tea differ from oolong teas?

Pu-erh undergoes a unique fermentation process, while oolong teas are partially oxidized. This fermentation gives pu-erh its distinct earthy flavor that many compare to the ripeness in viticulture. You’ll never go back to other varieties once you experience pu-erh’s complex profile.

3. Why are there different spellings for pu-erh tea?

The different spellings (pu-erh, puer, pu’er) come from translating Traditional Chinese characters into English. Each spelling is correct and refers to the same tea made in Yunnan, China.

4. What factors determine the grade of pu-erh tea?

The grade of tea depends on leaf quality, harvest time, and processing methods. Higher grades use tender leaves and buds, while lower grades might include larger, mature leaves. The art of tea grading is central to Chinese cuisine traditions.

5. Does pu-erh tea improve with age?

Yes! Pu-erh is one of the few teas that improves with age. Many collectors store their tea to accelerate the aging process naturally. The tea is generally more valuable and complex in flavor the longer it ages, making it highly sought after by tea enthusiasts.

References

- https://jyyna.co.uk/puerh-tea/ (2024-08-29)

- https://mansatea.com/blogs/learn/ripe-pu-erh?srsltid=AfmBOorrc6QK5AALWszGbDqTnIADpGu13-yOGTO_C4UcolbXKWueJR70

- https://puerhcraft.com/blogs/pu-erh-tea-news/pu-erh-tea-origins?srsltid=AfmBOoqze6-u-ExDtt7IMyrD5fCR-ze1EH2yMHSvRut4ICXsh7PdaIpi

- https://www.artoftea.com/blogs/tea-101/what-is-pu-erh-tea

- https://teatsy.com/blogs/blog/how-to-store-pu-erh-tea?srsltid=AfmBOoq5ujvUvyRIJ88RjnTLRvpF81W0SUyslkecfkZokmz07JfAcHka (2024-06-18)

- https://pathofcha.com/blogs/all-about-tea/storing-and-aging-pu-erh-tea-wet-vs-dry-storage-part-1?srsltid=AfmBOop5UnV5LxwsLnXGGVF3dsFKjD21YVQ9HgLCrTkD0vs6fxOE-vm4

- https://redblossomtea.com/blogs/red-blossom-blog/sheng-vs-shou-types-of-pu-erh-tea?srsltid=AfmBOoqBmxL0n3AJDaTnvhhtKaWkfKGAQ5qh6_ur3MaQmAGaEWkvSlmg (2017-11-29)

- https://white2tea.com/blogs/blog/ripe-puer-tea-a-beginners-guide-to-appreciating-shou (2023-10-12)

- https://www.borntea.com/blogs/tea/complete-guide-to-pu-erh-tea?srsltid=AfmBOooj9bcWM-AKVh1MemDSioIJiGxM2TzhVUMarlnAUuGICCOlih_r

- https://teasenz.eu/blogs/pu-erh-tea-101/processing?srsltid=AfmBOoqxRzDoiN4yqwSH7pV1zAHDGKIc7Vv6aAjbHy_z4vmaq500FQ1H

- https://mansatea.com/blogs/learn/pu-erh-tea?srsltid=AfmBOooSxCb62Bqr6pWpbuto17femult0M87YWeNlaD6jVjzUEB0HQej

- https://mansatea.com/blogs/learn/pu-erh-tea?srsltid=AfmBOorh5eGh28jOf2irDbX4lu8zJWtDvlfVltAbOyFqZmvgC-faR_nT

- https://teadb.org/some-thoughts-problems-about-traditionally-stored-puerh/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6222816/

- https://artfultea.com/blogs/tea-wisdom/raw-vs-ripe-pu-erh-whats-the-difference?srsltid=AfmBOoqbMLA9od14h2SOKU7zvhW4ZyTlLGgHgX_tHfjFVgEEMdI1uZ9S

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8909724/

- https://www.tealife.com.au/blogs/tea-recipes-and-journal/sheng-puer-tea-and-shou-puer-tea?srsltid=AfmBOooETUvO6LCGgtX_xCteu_YeVxCLBLo3Rxbbe9WVHjIvbc1_-Bw0

- https://mansatea.com/blogs/learn/pu-erh-tea?srsltid=AfmBOoo_dB1B31aJaFWh54a3DXQZgDO8MEt_fY_qs9Av5iTi6whO1E7R

- https://teadb.org/reading-drinking-numbers/

- https://pathofcha.com/blogs/all-about-tea/the-differences-between-raw-and-ripe-pu-erh-teas?srsltid=AfmBOoq5OhoQI5CJx_eUBt8Rd88UgoUr96zmbNqkMN3rYT7Tnwg7U_-m (2018-03-10)

- https://www.banateacompany.com/pages/criteria-choosing-pu-erh-tea.html?srsltid=AfmBOoqpn-57a3G4M0i18tGxc_XPo_Zo2b4lY0cWIqcCsRS54PEhIVTr

- https://yeeonteaco.com/blogs/news/six-famous-pu-erh-mountains?srsltid=AfmBOorfVpW8CYGdpzvMWCN1e9taen62KqbQpNdqs-HGRLVRWZHHgL-v

- https://yunnansourcing.com/collections/menghai-tea-factory-pu-erh?srsltid=AfmBOop1oWKIHUlqRY8-6cf-21lTeQDhMjiKgrOM3Zz5kEKq0HAwu_ZM

- https://teasenz.eu/blogs/tea-magazine/lincang?srsltid=AfmBOoob9rnP9MikAjnxinC3OMqWyZEJQeg8VemFF5HjC_5ya9oFQ3-g

- https://teasenz.eu/blogs/tea-magazine/xishuangbanna?srsltid=AfmBOoodHJzKpVOdwJgDkEvbbRP-R4Dvcia9raEKf8SvvmGCHFxX1Feg

- https://puerhcraft.com/products/old-tree-puer-raw-tea?srsltid=AfmBOorYgnX6F3jMeeTpvNeJ5zoh6Xz0KY35Q82YtN6kn_C2hoBo7H6B

- https://crimsonlotustea.com/blogs/puerh/13981917-bulang-mountain-puerh (2014-04-29)

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11754136/

- https://riversandlakestea.net/nannuo-puerh-selection/

- https://www.teavivre.com/info/overview-of-jingmai-tea-area.html?srsltid=AfmBOoq4dJKwR24dnKy0XxTqT-hLCRqGSisePO-aEYywXqg4NAxtHUFp

- https://www.tea-and-mountain-journals.com/lao-ban-zhang-pu-erh

- https://chasourcing.com/collections/puerh-tea/lao-ban-zhang-puerh-tea/?srsltid=AfmBOooQJW0erwCuB4oZOchi9FvjT8_SWBlJeOZyQuGro95GJj4fPMRV

- https://yeeonteaco.com/blogs/news/traditional-hong-kong-puerh-storage?srsltid=AfmBOoqFZRUfnAL5hNKSr0o3DkXVssrtDvBA8ILoWj3G62EQcXPiNkdr

- https://yeeonteaco.com/blogs/news/traditional-hong-kong-puerh-storage?srsltid=AfmBOorZYOCkSjZehF3UfKm0SqzeGw1qqzuysfQTIEI-Z2OBVu78fpac

- https://pathofcha.com/blogs/all-about-tea/aging-pu-erh-tea-wet-storage-vs-dry-storage-part-2?srsltid=AfmBOoqDiGFQ2zTynvc8qQq3jozfDMz5U-djvPA0SYnyUxt_UKjKjgG_ (2022-05-15)

- https://marshaln.com/2008/11/wednesday-november-12-2008/

- https://pathofcha.com/blogs/all-about-tea/storing-and-aging-pu-erh-tea-wet-vs-dry-storage-part-1?srsltid=AfmBOoodCQxM28CcDxO6k-LMyXfkfmA9bHKk_rWW1m5e1z3zjJJWElYn

- https://ooika.co/learn/puer-tea-cake?srsltid=AfmBOoqCu0zi97MSHeUClpr8aeMbk1d-dDuTNfzZOXMoT7L5YaViCu0B

- https://www.thespruceeats.com/what-is-pu-erh-tea-766434 (2022-09-20)

- https://cspuerh.com/blogs/tea-101/exploring-the-different-shapes-of-pu-erh-tea-cakes-bricks-and-tuocha-explained?srsltid=AfmBOorqMOIqKEuMyqjLlU1L1Pix3cd_lCyb0lZgYHJvQFZiAFHyWZ7k

- https://helloteacup.com/2019/03/24/different-shapes-of-pu-erh-tea/ (2019-03-24)

- https://pathofcha.com/collections/pu-erh-teas?srsltid=AfmBOoo0E52sYK3ZC3Q5MfqmSSPyQ7Xip4yT3_0zzN3kls3yOLg5aLsn

- https://www.borntea.com/blogs/tea/complete-guide-to-pu-erh-tea?srsltid=AfmBOoouowxS-G9RPpdc8-ZKgq0dAftSlezdf7pb-9zedZnlQ3bOc-g-

- https://cspuerh.com/blogs/tea-101/a-beginner-s-guide-to-pu-erh-tea-tasting-how-to-develop-your-palate?srsltid=AfmBOooYHYDQJW7t9PspUByVlx8NYold8qB_h6qh6ustx21qsr245KSh

- https://cspuerh.com/blogs/news/how-to-identify-authentic-pu-erh-tea-a-buyer-s-guide?srsltid=AfmBOorYxQWGrv3MmI1SNWi0y-OX88b3_Jk9P0HZ-CYDAmibuySyCHSK

- https://cspuerh.com/blogs/news/how-to-identify-authentic-pu-erh-tea-a-buyer-s-guide?srsltid=AfmBOorQjw2JKGT1OlKGtO18dDJ33NlYRS-7NGDVcJry1Q0qY8kOq4wg

- https://tea-side.com/blog/over-steep-good-tea/

- https://www.teavivre.com/info/temperature-the-most-mysterious-things-for-pu-erh.html?srsltid=AfmBOoqjhLwOfFpR0B3GtB2tqrvbeTR2wNqez8SPN15Y7pRlIHV33eIo

- https://steepster.com/discuss/1818-multiple-steepings-of-pu-erh

- https://teasenz.eu/blogs/pu-erh-tea-101/how-to-brew-pu-erh-tea?srsltid=AfmBOooxeem4VP9YSlKqzJuBqTN_UaI392X55IZT8PmM07VT7DJcZ3P0

- https://teainspoons.com/2021/08/26/an-introduction-to-puerh-teas/ (2021-08-26)

- https://www.borntea.com/blogs/tea/complete-guide-to-pu-erh-tea?srsltid=AfmBOooFMAD-nNTRUu71y9A6iBs_246ZXp3rMYmHkrqGqDBfmYI9vFx8

- https://puerhcraft.com/blogs/pu-erh-tea-news/pu-erh-tea-origins?srsltid=AfmBOoqG8umVU-O7ZLg3pmeFBxFPxcm8Sz_zHbJ0EQnuF25sth53_3cM

- https://www.borntea.com/blogs/tea/complete-guide-to-pu-erh-tea?srsltid=AfmBOoououEmwUcMLTpU8ecAmk8zXrDnDvUuRCNFJjNr5DJd99RoJ4XX